It’s amazing how little changes over time.

There are a few kinds of movies I’m always going to be interested in. I love a war movie. When I hear of a new one coming out, I always eagerly await the reviews, decide to watch it anyway, and if it does disappoint, I keep my head up looking for the next Saving Private Ryan, Black Hawk Down, Dunkirk, or The Covenant, when, sadly, we have a lot of Jarhead 2s and Hacksaw Ridges. I love a whodunnit, I’ve seen all the Branagh Poirot movies at least twice and I tell anyone who will listen that See How They Run is an underrated gem. I also love movies about curmudgeonly writers, but I feel like if I said why, that would be telling.

But I’m not here to talk about any of those kinds of movies. I want to talk about another kind of movie that I love—reporter films. It’s not something we see too often anymore (though it seems they’re making a comeback), but as a kid, reporter was always one of those things I wanted to grow up to be, along with astronaut baseball player and moon knight (not the superhero Moon Knight, mind you, a knight on the moon who rides a space dragon), as well as a brief stint wanting to be a chaotician, so when a good reporter film comes along, they’ve got me hook, line, and sinker. I love seeing an overworked, underpaid underdog taking on the system to get the truth to the people. I especially love it if they’re exposing corruption and conspiracies, but it doesn’t always have to be so grandiose. I don’t always need it to be as hefty as Spotlight or State of Play, or as understatedly brilliant and touching as Safety Not Guaranteed, or as significant in scope as Frost/Nixon or Zodiac. Because when it comes to those fighting for the truth, it is always hefty, it is always touching, it is always significant; to me, at least.

And that brings me to The Paper, a movie that I’ve had in my Netflix queue for weeks, but I could never find myself in the right mood for until it got the dreaded “Leaving Soon” tag on the thumbnail. Of course, the way streaming services work, it’s likely only a matter of time until it pops up on some other streamer, so I could always go on the hunt for it again in a few weeks (don’t you love the freedom of cable cutting?), but I found the two hours or so and decided to put down Astro Bot and watch it.

Boy am I glad I did.

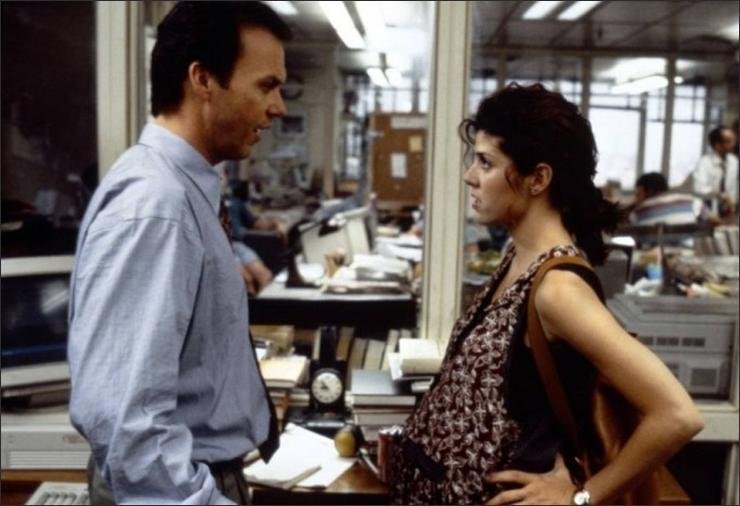

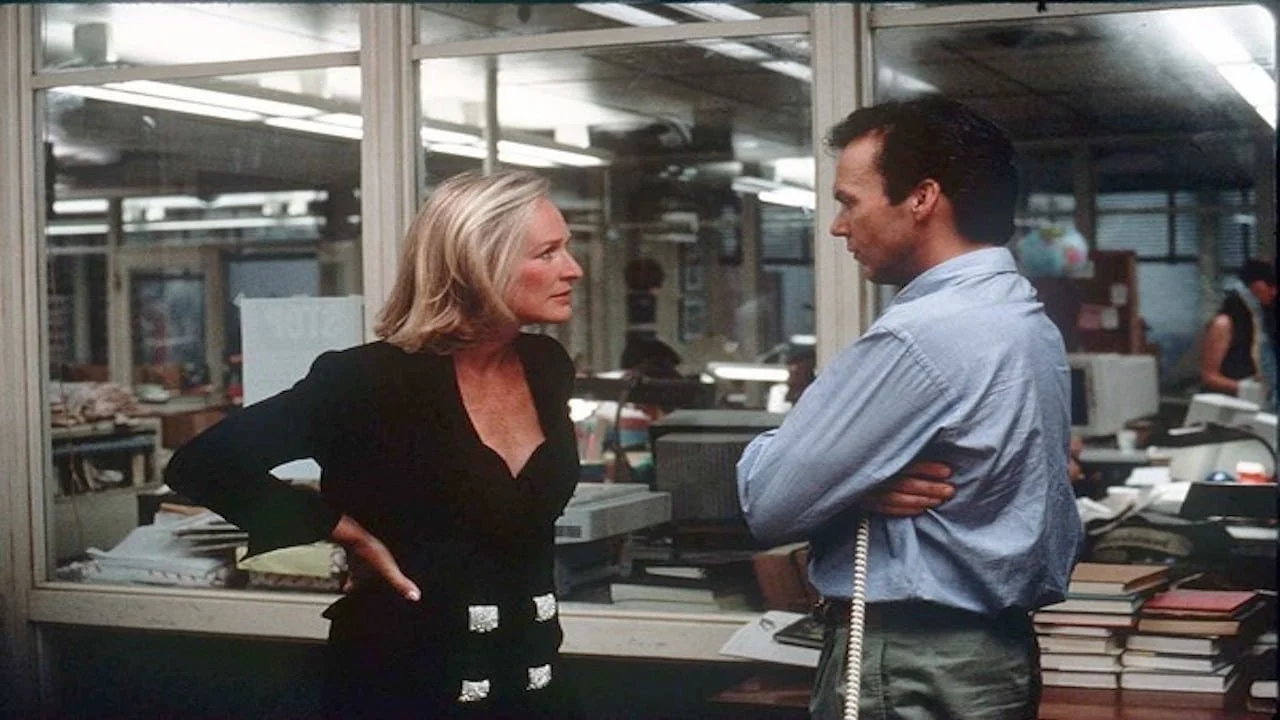

For those unfamiliar, like I was, The Paper is a 1994 film about a struggling New York newspaper that is a stand-in for the New York Post, taking place over a 24 hour period, or one news cycle, which is how the news used to be before 24 hour news channels and eventually Twitter changed the entire scene. We open on two young Black men stumbling across a vandalized car with anti-white slurs painted on it. They think the occupants are asleep, so they approached the car to wake them up and tell them that it’s not that safe a place to bivouac for the night and they should probably move on. But in the car were two slain white men and beside it, a discarded MAC-11 lying on the sidewalk. As one man reaches for the gun, the other tells him not to, and a witness stumbles upon the scene, causing the Black men to flee in fear of being held responsible for the double homicide they did not commit. More on this later. Then we get to see Henry Hackett, played by Michael Keaton, whom, depending on how old you are, you may remember as Batman, Beetlejuice, Birdman, or if you’re one of the unfortunate few who also sat through The Flash, old Batman. You may also recognize him from Spotlight, another excellent film in which Keaton plays a dedicated newsman. He wakes up next to his seriously pregnant wife (played by Marisa Tomei), fully dressed, and very deeply in trouble with her. You see, in addition to being the metro editor for a troubled paper, he’s also about to become a father for the first time and his wife is worried—and scared—that she’s going to lose her career, also as a reporter, and end up raising their child with an absentee father and partner because he’s always at the office. Rounding out the cast is not only a ton of talent you’ll recognize, namely Glenn Close, Robert Duvall, and Randy Quaid, but also a veritable who’s who of slightly younger than you remember them white guys, such as the bad guy from Mr. Robot, Gil from Frasier, that cop from an episode of Monk where he briefly rejoins the force, and another guy who was also in Spotlight. There was definitely a lot of “Oh, I know that guy, he’s the one who does the Nixon impression in that episode of Parks & Rec”, but overall it was a reasonably diverse cast for 1994, including Geoffrey Owens and Roma Maffia, and I commend them for that. With these older movies, you take what you can get; diversity wasn’t a priority in the 90s, so when you see anything even reasonably diverse, it’s memorable.

What is also memorable is what hasn’t changed. Young Black men are still blamed for crime, the NYPD still busts down your door with guns drawn no matter who is in the room, and the truth is still a fight. It’s a story as old as stories about the news—business wants while the news needs. The paper, the New York Sun, is recovering from teetering on the edge of shutting up shop when the business-minded paper savior and managing editor Glenn Close brings them back from the edge, but only just. And here it is. Here is the crux of the story, the spool around which all the threads are wrapped. The news needs the truth; the news needs accuracy, clarity, timeliness, and diligence. And all these needs cost money. Business wants profits. In order to maximize profits, it’s usually the needs of the news that suffer. Business wants, the news needs. It’s hard not to see the tension and how both sides here have genuine pros and cons; Close may be the antagonist in the film, but she’s hardly villainous. After all, you can’t have the paper if you can’t keep the lights on and put ink on the page. So in order to have independent journalism, you need to have someone footing the bill. But there needs to be balance—all too often now, business seems to take the forefront. Sensationalism is the word of the day; if it bleeds, it leads, but even better now if it makes you angry. In an era where the truth has become malleable, where total fictions and outright lies are run with loudly and corrected quietly, and misinformation and disinformation are beamed to your phone in an instant, The Paper seems more relevant than ever.

In a way, it’s a love letter to journalism, including the dirty side of it. The Paper doesn’t shy away from the characters’ personal struggles and faults. Glenn Close is having an affair with a reporter. Robert Duvall has an estranged daughter and a prostate the size of a bagel, according to him. Marisa Tomei is nigh on petrified that she’ll be raising their child alone, losing her identity in the process. Keaton wants to be there for his family, but constantly ignores the concerns of his wife because of his dedication to the paper; so much so that he steals a lead from competing paper The Sentinel, while there on a job interview for a job that Tomei desperately wants him to take because it means better hours and more money for their nascent family. Randy Quaid’s character is a needed bit of comic relief in what is ostensibly a comedy, but even he has his troubles—we meet him sleeping on Keaton’s office sofa with a revolver tucked into his pants because he believes the civil servant he’s been lambasting in his column is coming after him. These people do a thankless job with little pay and great personal sacrifice; at least when it’s being done right. The movie still finds the comedy in their situation, though. Through all this, there are plenty of laughs to be had, but it’s not the thing about this film that really stuck out to me; it’s how even thirty years later, these stories still feel familiar, not because they’re overused tropes, but because they’re still relevant. Because we’re still facing them. Because not enough has changed. Print media is still in peril. The truth is still under attack. Profits are still being prioritized. The police and public are still all too happy to blame the closest Black person for crime, and the cops still come through the door in a way that makes every arrest feel like it could end up like Two Distant Strangers.

Now that campaigning politicians can lie, admit it’s a lie, and continue to run on the admitted lie and people believe them, it may seem quaint for reporters to come to literal blows over a headline painting two innocent kids as murderers being brought to justice, but the fight for truth has to happen on every level. Shades of the Central Park Five loom over the lead story in The Paper, but beyond that, we know here, as viewers, that the two teenagers accused of the murder are innocent, but we’re not the only ones. After hearing some chatter on the police scanner, Quaid is convinced that not only is the arrest bogus, the cops know it’s bogus, and the arrests are just for optics. But, Close wants to run a gotcha headline because they got pipped to the post the day before on the actual murders; and I mean she literally wants to run a photo of the suspects doing the perp walk to the prison bus with the headline of “GOTCHA!” plastered across the front page. News reports running in the background televisions have interviews with people cancelling plans to come to New York; tourism dollars were starting to become a concern citywide because the murders and news coverage were stoking racial tensions. Pressure on all sides. Keaton decides to step up, running with Quaid’s intuition, but doesn’t have the proof. But like any dedicated journalist, he’s determined to get it.

The story has lots of plot points that weave together, but it all comes to a head when, two hours after they’re supposed go to the presses, let’s just say that Keaton and Close make more than impassioned arguments for their side. And what ensues, well, that just needs to be experienced without me tinting anything for you. But what I will say is that while The Paper may be a forgotten film, overshadowed by other blockbusters from 1994 like The Lion King, Forrest Gump, True Lies, Clear and Present Danger, and Speed, this is a movie that holds up to the test of time and—in the current news climate—is more than relevant, it’s important. The Paper leaves Netflix on September 30th, so I haven’t given you a very large window, but like I said, if you miss it, keep it on your watchlist. It’ll show up somewhere soon enough and it is absolutely worth your time. Because good journalism is as important as ever and this movie acts as a well needed reminder.